05: Basic Mathematical Operations & Debugging

Learning Outcomes

- Be able to use python as a calculator

- Understand logical and boolean operations available

- lazy boolean evaluation

- Read a traceback to debug code

- Basic loop, control & indentation

- Simple printing / formatting

- Multiple assignment

Contents

- This will become a table of contents (this text will be scraped).

Python as Calculator

The interpreter acts as a simple calculator: you can type an expression at it and it will write the value. Expression syntax

is straightforward: the operators +, -, *, ** and / work just like in most other languages (for example, Pascal or C); parentheses () can be used for grouping. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

spam = 2

eggs = 7

[

spam * eggs,

-eggs**spam, # note that - has a lower priority to **

eggs - spam**spam,

eggs * (1 - spam),

eggs % spam, # remainder

eggs // spam # floor division (integer division)

]

[14, -49, 3, -7, 1, 3]

This return structure is a unique python object called a list. We have also introduced the idea of assignment i.e. assigning a value to a variable name (Later we will see that this is not limited to numbers)

Style Tip Always add a single space around mathematical operators unless you want to emphasise which get enacted first e.g. eggs - spam**spam helps the reader see that spam**spam is evaluated first. Please briefly read: https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/#other-recommendations for a guide on how to write expressions

Similarly there are a number of logical operations

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

spam = 2

eggs = 7

[

eggs > spam,

eggs < spam,

eggs != spam,

eggs == spam,

eggs >= spam,

eggs <= spam,

]

[True, False, True, False, True, False]

and boolean operations

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

spam = 0

eggs = 7

[

eggs and spam,

eggs or spam,

eggs & spam, # bitwise and

eggs | spam, # bitwise or

not eggs,

(not eggs) and spam,

not (eggs and spam),

# for a real bit of banter ~ is the operator for: (-x)-1

~eggs,

(~~eggs) == eggs, # which is symmetric

(not(not eggs)) == eggs # unlike not

]

[0, 7, 0, 7, False, False, True, -8, True, False]

Style Tip Note how I indent the contents of large lists by four spaces. This makes it easier to read and also easier to comment on things within the list

Lazy Boolean Evaluation

A huge source of errors in python… the following will evaluate!!

1

eggs > spam or an_undefined_variable

True

but in contrast

1

eggs > spam | an_undefined_variable

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-116-3eba06dec764> in <module>()

----> 1 eggs > spam | an_undefined_variable

NameError: name 'an_undefined_variable' is not defined

This is because and and or are evaluated lazily. If there is no need to evaluate the second expression then it won’t ever hit the compiler. Their bitwise counterparts & and repsectively | will always evaluate the entire line.

This property is very useful, however. Imagine if the second condition took 1hr to evaluate!

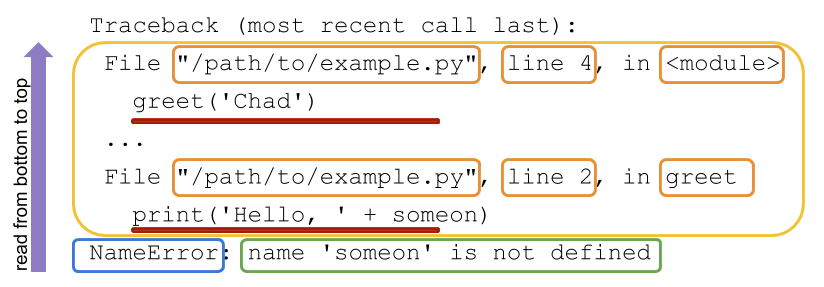

The traceback

You will notice the traceback in the example above. The following is a guide on how to read the traceback

In Python, it’s best to read the traceback from the bottom up:

-

Blue box: The last line of the traceback is the error message line. It contains the exception name that was raised.

-

Green box: After the exception name is the error message. This message usually contains helpful information for understanding the reason for the exception being raised.

-

Yellow box: Further up the traceback are the various function calls moving from bottom to top, most recent to least recent. These calls are represented by two-line entries for each call. The first line of each call contains information like the file name, line number, and module name, all specifying where the code can be found.

-

Red underline: The second line for these calls contains the actual code that was executed.

The way I personally read tracebacks is as follows:

- Blue box - what error is this?

- Green box - is this error description obvious?

- read next red underline starting from bottom - what caused it?

- Is the line of code a line of code you wrote or something reall obscure?

- If not obscure… i. orange box - If the error is here, go to the file and on this line correct the error ii. If you don’t recognise the line of code google it

- If obscure and you can go up one line, goto 3. and loop

- If you run out of lines then google the Blue and green box ommiting any specific variables (e.g. I wouldn’t include

'someon'in my google search but I would include the rest) - If that doesn’t yeild results start at the top orange box and replicate each function call working to the bottom

Golden rules of debugging

- The machine is always right It will tell you precisely what you asked

- The machine doesn’t read your mind What you wanted is not usually aligned to what you asked

- Accept your stupidity self-loathing is a common side effect to debugging. Just try not to swear in public places

- Don’t be arrogant 50% of the time your code is wrong every time

Example: Fibonacci Series

The sum of two elements defines the next.

1

2

3

4

a, b, = 0, 1

while a < 10:

print(a)

a, b = b, a + b

0

1

1

2

3

5

8

This example introduces several new features.

Multiple assignment

The first line contains a multiple assignment: the variables a and b simultaneously get the new values 0 and 1. Expressions on the right-hand side are all evaluated first before any of the assignments take place. The right-hand side expressions are evaluated from the left to the right.

Simple Loops

The while loop executes as long as the condition a < 10 remains True. Any sequence or number with a non-zero length is true, empty sequences are false. The standard comparison operators are written the same as in C: < (less than), > (greater than), == (equal to), <= (less than or equal to), >= (greater than or equal to) and != (not equal to).

Printing

The print() function writes the value of the argument(s) it is given. You can format strings like

1

print('this is a decimal third: {0:10.4f}'.format(-1/3))

this is a decimal third: -0.3333

- Where the

f10.4indicates that we want to output afloat(a decimal) with length no less than10(including the-and.) with a4decimals. - To the left of the colon this is the argument number (zero starting) in

.format(arg0, arg1)that you wish to be inserted here. - Blank on the left of

:will just take arguments in order. - Blank on the right will just format as if you did

str(-1/3)

Indentation / the colon :

The body of the loop is indented: indentation is Python’s way of grouping statements. You must indent with 4 spaces for each indented line. Each line within a basic block must be indented by the same amount.

In addition to being used in formatting… The : symbol is used to start an indent suite of statements in case of: if, while, for, def and class statements. Everything following this : should be indented by 4 spaces.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

eggs = 4

bacon = 2

if eggs and bacon:

print('eggs and bacon')

while bacon < eggs:

print('{} {}'.format(bacon, eggs))

bacon +=1

eggs and bacon

2 4

3 4

As a sneak peak at indentations we will use later…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

iterable = 'string'

# enumerate will return [(0, item_0), (1, item_1), ..., (n, item_n)]

# from an iterable that is [item_0, item_1, ..., item_n]

for i, s in enumerate(iterable): # remember multiple assignment? assign i, s = n, item_n

# d means format as integer. 02d means ensure length of 2, padded with 0

print('Num: {1:02d} char: {0:s}'.format(s, i))

def my_func(x):

return x**2

class MyClass:

def another_func(self, y):

return my_func(self)

Num: 00 char: s

Num: 01 char: t

Num: 02 char: r

Num: 03 char: i

Num: 04 char: n

Num: 05 char: g

Exercises

It is assumed that you will get multiple tracebacks in the questions. Some will be very long and really obscure - stick to the recipie above and you should surface!

For these exercises, we will use ipython. You may need to pip install it, google how to do this and once installed you can simply type

1

ipython

in the terminal

Exercise 5.1: Debugging confusing code

This example shows some code that you may not understand. This is common when using libraries such as pandas and numpy which may throw some really obscure errors. This exercise is to help you realise that all problems are debuggable if you read the traceback carefully and don’t get bogged down in that what you may not understand.

Hint Don’t skip any steps when reading the stack! You can insert print and type functions by inserting them (with 4 space indentation) to help debug errors like

1

2

3

4

def my_func(a, b):

print('a is:', a)

print('a has the type of:', type(a))

return second_func(x, y)

Here is the question… Understand why the below function does’t return 25 and fix the issue below. You will need to run the functions below in python

Trick In ipython you can copy blocks of python code to your clipboard and paste them directly in by typing %paste in the ipython terminal

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

def first_func(x, y):

return second_func(x, y)

def second_func(a, b):

return third_func('a', 'b')

def third_func(a, b):

return a**b

and the executing the following line

1

>>> first_func(5, 2)

will give the error you need to fix as below

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-6-710f1e0a547e> in <module>()

----> 1 first_func(5, 2)

<ipython-input-5-a33026a6e4d1> in first_func(x, y)

1 def first_func(x, y):

----> 2 return second_func(x, y)

3

4 def second_func(a, b):

5 return third_func('a', 'b')

<ipython-input-5-a33026a6e4d1> in second_func(a, b)

3

4 def second_func(a, b):

----> 5 return third_func('a', 'b')

6

7 def third_func(a, b):

<ipython-input-5-a33026a6e4d1> in third_func(a, b)

6

7 def third_func(a, b):

----> 8 return a**b

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for ** or pow(): 'str' and 'str'

1

# Solve me!

Exercise 5.2: Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM)

This exercise builds on your ability to translate mathematical operations into code

In this exercise we will look at solving the recursive equation for brownian motion, which can be used to model an asset price

$S_{t+1} = S_t e^{(r - \ frac{1}{2} \ sigma^2) \ Delta t + \ sigma \ epsilon \ sqrt{ \ Delta t}}$

To do so we introduce the numpy library and note that you can rename library names on import with as to make it more convinient. Traditionally, most users will rename numpy as np

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

import numpy as np # style tip: Put imports at the top and separate from statements

np.random.seed(42) # Popularity tip: Always use 42 as a random seed.

sigma = 0.1 # annualised volatility of 10%

epsilon = np.random.standard_normal()

s_t = 100

dt = 1/252 # using annualised vol so need days as frac of yr

r = 0.02 # annualised expected return

Exercise 5.2.1: Calculate the value of $S_{t+1}$ for a single time step

Use the function np.exp() as the exponential function e and np.sqrt for the squareroot function

1

# Solve me!

Your answer should be exactly (the last digit may be different but no others!)

1

100.31936176261115

Exercise 5.2.2: GBM for an Equity

This exercise will reinforce the learning in 5.2.2 and also require knowledge of the boolean operations covered earlier in this section.

Equities cannot have a value less than zero, $S_{t} \ ge0 \ \ forall t$

Lets increase the volatility $\sigma$ significantly to 1000% and now model the stock price until it goes to zero.

Modify the earlier Fibonacci Series example to loop the calculation of $S_{t+1}$:

- Set

sigmato have a value of 1000% - print the current price

s_tat each time step - Stop the simulation once the stock price reaches zero

Hint Remember that you can reassign the variable s_t and you will want a new epsilon = np.random.standard_normal() to be calculated at each iteration. Also using 0 exactly might take a while to converge, for example $10^{-250}$ is still not zero but in finance anything less than $0.01 is essentially zero. Another way you can represent 0.01 is in exponential form as 1e-2 which stands for $10^{-2}$

1

# Solve me!

This example should frustrate you. Bear in mind that frustration is part of the journey and don’t be afraid to ask. If you don’t mess up, you won’t learn!

To check your solution, you should get exactly the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

100

112.13879641805384

84.29357966694793

103.95704620173869

222.53025983690668

157.4687454246345

111.43051850624998

247.12109431827315

328.64678816306173

200.519035767586

231.44830683293753

141.75461677171188

86.6937688048521

82.80352071570734

20.345992875883873

5.629128022692305

3.239481761504343

1.4036225060502883

1.4030946735581837

0.6494337451435577

0.2187872467390197

0.4517091002626084

0.3213334455297651

0.2749762670387091

0.0919131825252341

0.05349468201249927

0.04704589325853863

0.01868521263246368

0.019415400963917445

0.010906582129479083

Next Topic